Dr Isaacson: Hi, I’m Stuart Isaacson, a clinical associate professor of neurology at the Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine at Florida International University in Miami. I’m also director of the Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Center in Boca Raton. As a movement neurologist, I’ve long been interested in involuntary movements and the intersection between psychiatry and neurology.

Dr Jain: And my name is Rakesh Jain. I am a clinical professor of psychiatry at Texas Tech University School of Medicine in the Permian Basin and also have a private practice in Austin, Texas, focusing on tardive dyskinesia.

Dr Isaacson: Rakesh, why is it important to understand the pharmacology and pathophysiology behind tardive dyskinesia?

Dr Jain: Well, I do think it’s critical for prescribers, be they in psychiatry or any other specialty, to understand the neurobiological mechanisms of tardive dyskinesia and how it differs from other drug-induced movement disorders, particularly drug-induced parkinsonism.

Recognizing tardive dyskinesia as a hyperdopaminergic disorder and juxtaposing it with the hypodopaminergic pathophysiology of drug-induced parkinsonism provides us with a foundation for selecting appropriate tardive dyskinesia treatment options for patients on dopamine receptor blocking agents.1

It’s not just an academic conversation. It actually helps us determine which treatment to offer, and a mistake here can potentially have consequences in some instances.

Dr Isaacson: And I think it’s important to note that all dopamine receptor blocking agents can cause tardive dyskinesia, and may occur in up to 30% of patients taking dopamine receptor blocking agents.2 And once it occurs, it may be irreversible.3,4 We may see less or more over time, depending on how we adjust the medications.4 But it seems to always be there when provoked.

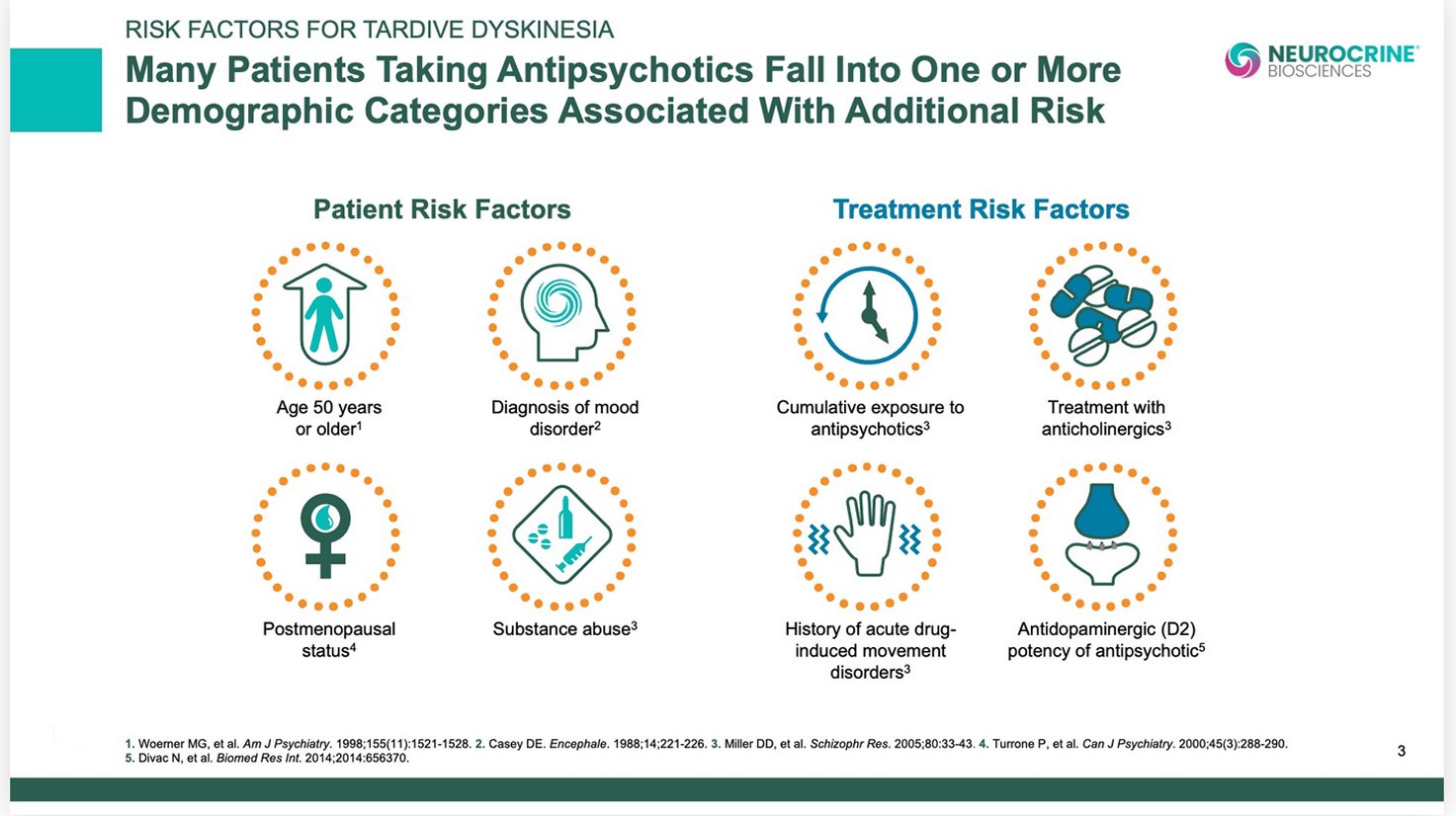

And unfortunately, we don’t know how to predict very well who will be affected, despite understanding some of the risk factors.

Dr Jain: Stuart, before we go deeper, maybe you can explain what tardive dyskinesia is, and how it’s related to dopamine?

Dr Isaacson: Well, there are 2 main types of abnormal movements. Some are too much movement, or hyperkinetic, and some are too little movement, or hypokinetic. Too little movement is what we mean by parkinsonism.1,5 Too much movement is a number of different hyperkinetic disorders, with tardive dyskinesia being one of them.5,6

We think tardive dyskinesia is probably from overactivity of the dopamine system: too much dopamine.5,6 And we believe that tardive dyskinesia arises from prolonged exposure to dopamine receptor blocking agents such as antipsychotics.2

Dr Jain: And how might dopamine receptor blocking agents lead to symptoms of tardive dyskinesia?

Dr Isaacson: Well, blockade of dopamine D2 receptors over time may cause the brain to adapt and results in a hypersensitivity or an upregulation of these receptors, with the consequence of driving these motor pathways to hyperkinetic movements, such as involuntary tardive dyskinesia movements.5,6

Of course, tardive means delayed, and we tend to see this type of upregulation occur after months or years.5,6 Not usually acutely.

And when we lower the dose of the dopamine receptor blocking agent, we might wind up with more movement temporarily as we remove some of the blockade on these upregulated, hypersensitive dopamine receptors.1

So Rakesh, can you explain why dopamine affects both neuropsychiatric symptoms and motor activity?

Dr Jain: Yes. Dopamine is a very hardworking neurotransmitter. It seems to do heavy lifting on many normal human functions, such as thought, motivation, and mood.7 So dopamine abnormalities often lead to challenging disorders that are very common in psychiatry: schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and complex mood disorders.8-10

But at the same time, dopamine affects motor activity. This same neurotransmitter lives in both the ventral striatum and the dorsal striatum. In the dorsal striatum, dopamine is involved in the control and regulation of voluntary movements.5

So when we offer our patients interventions to treat their psychiatric pathology, trying to alter their dopamine function in the ventral striatum, inadvertently we end up disturbing dopamine regulation in the dorsal striatum.5

As we mentioned, tardive dyskinesia appears to be a disorder of a dysregulated dopaminergic system in that part of the brain, which leads to those very classic abnormal movements, as well as the potential impairment that arises from it in some patients.1,5,6,11

So dopamine does appear to be a great unifier between psychiatry and neurology.

Dr Isaacson: It really highlights that there’s more than one dopamine pathway. Traditionally we have looked at the nigrostriatal pathway on the neurology side and the mesolimbic pathway on the psychiatry side. But there’s really interplay between them.7

Dr Jain: Stuart, how does dopamine’s signaling within the motor striatum affect motor symptoms?

Dr Isaacson: Well in parkinsonism, whether it’s Parkinson’s disease or drug-induced parkinsonism, we think about too little dopamine, either from blockade of dopamine or due to a loss of dopamine-producing cells.1,4

But we also have to think that too much dopamine can cause too much movement from the striatum. And the nigrostriatal system really controls initiation of movement and normal flow of movement. When there’s too little dopamine, there’s too little movement. And then, when there’s an acute blockade of dopamine receptors, there might be too little movement.1,5

So both the presynaptic and postsynaptic systems can lead to these problems. It’s really a focus on the nigrostriatal pathway.

Dr Jain: So in the nigrostriatal pathway, the blockade of dopamine D2 receptors, when it is acute, can produce parkinsonian symptoms.5

But without even changing that blockade, prolonged exposure to D2 blockade can morph in terms of the phenotype, in terms of what the body shows, from too little to too much dopamine signaling.5,12,13 We may think that we have to do something different to cause tardive dyskinesia, but that’s in fact not true.

Dr Isaacson: So Rakesh, can you explain how that morphing happens from one movement disorder to another?

Dr Jain: I think the answer is that the occupation or blockade of a receptor, reducing the receptor, can have acute, subacute, and tardive effects. And they can all be quite different from each other.14

You can actually acutely get akathisia. You can subacutely or acutely get parkinsonian symptoms. And that very same blockade of the D2 receptor, instead of reducing motor movement, can actually lead to uncontrolled excessive movement, which then, of course, phenotypically becomes tardive dyskinesia.

So the thinking is that when you offer an antagonist to a receptor, the activity of the receptor goes down, which is thought to lead to improvement in neuropsychiatric symptoms. But it also is the very reason you can have the onset of, say, something like drug-induced parkinsonian symptoms.5

But those same receptors, once they are occupied for a prolonged period, can actually morph into an upregulated state.5,12,13 And any receptor or any family of receptors, when they are upregulated postsynaptically, can then lead to an increase in neuronal activity.

And let’s not forget that dopamine neurons in the dorsal striatum are involved in controlling motor movements.5 If they’re upregulated, quite logically, the result will be excessive movement of the motor muscles.

But this is a fairly incomplete hypothesis, and there are competing hypotheses in the scientific community. There’s a glutamate hypothesis, there’s a GABA hypothesis, there’s an antioxidant hypothesis.1 So that’s important to remember.

But though there is still much to learn, it is critical for prescribers to be aware of the proposed neurobiological mechanisms of tardive dyskinesia and how they differ from other drug-induced movement disorders. This understanding provides the foundation for selecting appropriate treatment options for patients with these conditions.1

Please explore the other resources available on this website for more detailed information on identifying and diagnosing tardive dyskinesia.